Semi-sparsity for Smoothing Filters

Abstract:

We propose an interesting semi-sparsity smoothing algorithm based on a novel sparsity-inducing optimization framework. This method is derived from the multiple observations, that is, semi-sparsity prior knowledge is more universally applicable, especially in areas where sparsity is not fully admitted, such as polynomial-smoothing surfaces. We illustrate that this semi-sparsity can be identified into a generalized $L_0$-norm minimization in higher-order gradient domains, thereby giving rise to a new “feature-aware” filtering method with a powerful simultaneous-fitting ability in both sparse features (singularities and sharpening edges) and non-sparse regions (polynomial-smoothing surfaces). Notice that a direct solver is always unavailable due to the non-convexity and combinatorial nature of $L_0$-norm minimization. Instead, we solve the model based on an efficient half-quadratic splitting minimization with fast Fourier transforms (FFTs) for acceleration. We finally demonstrate its versatility and many benefits to a series of signal/image processing and computer vision applications.

Introduction

Filtering techniques, especially the feature-preserving algorithms, have been used as basic tools in signal/image processing fields. This favor is largely due to the fact that a variety of natural signals and visual clues (surfaces, depth, color, and lighting, etc.) tend to spatially have piece-wise constant or smoothing property, between which a minority of corner points and edges — known as sparse singularities or features formed by discontinuous boundaries convey an important proportion of useful information. On the basis of this prior knowledge, many filtering methods are promoted to have “feature-preserving” properties to preserve the sparse features while decoupling the local details or unexpected noise. The prevailing use of “feature-preserving” filtering methods is also found in many applications, including image denoise

In the paper, we propose a semi-sparse minimization scheme for a type of smoothing filters. This new model is motivated by the sparsity-inducing priors used in recent cutting-edge filtering methods

Observations:

The \(L_0\) norm counts the number of its non-zero entries, which directly measures the degree of sparsity of the vector. As a metric, it has been proved to be capable of capturing the singularities and discontinues of signals. In signal and image processing, a corresponding \(L_0\) regularization is always a favorable and powerful mathematical tool to formulate the sparsity-induced priors. It has been used in a huge amount of existing works, including sparse signal/image recovering

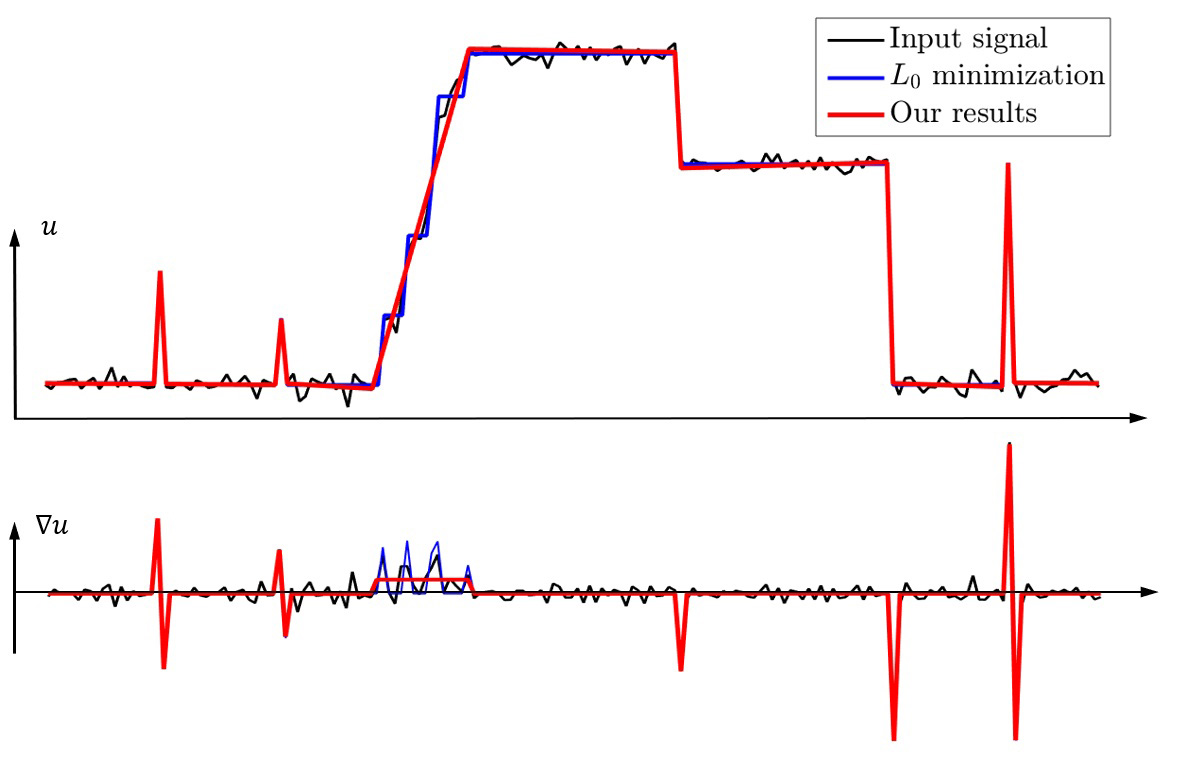

As interpreted in Fig. 1, the non-zero elements of gradient \(\nabla u\) is not fully sparse but are densely distributed in some region. We say \(u\) is a so-called semi-sparse signal in gradient domains in this case. On the other hand, it is easy to verify that the second order gradient \({\Delta u}\) is sparse. Without loss of generality, we define that \(u\) is a semi-sparse signal, if the higher-order gradients \({\nabla}^{n-1} u\) and \({\nabla}^{n} u\) satisfy,

\[\begin{equation}\label{eq:4} \begin{aligned} \begin{cases} & {\left\Vert \nabla^{n} u\right\Vert}_0 < M,\\ &{\left\Vert \nabla^{n-1} u\right\Vert}_0 > N. \end{cases} \end{aligned} \end{equation}\]where, \({\nabla}^{n}\) is a \(n\)-th (partial) differential operator, and \(M, N\) are some appropriate natural number with \({M\ll N}\). The idea of Eq. (4) is easy to understand, that is, the energy of \({\nabla}^{n} u\) is much smaller than that of \({\nabla}^{n-1} u\). Intuitively, this happens if and only if the support\footnote{The support of vector \(u\) is its number non-zeros elements.} of \({\nabla}^{n} u\) is much less than that \({\nabla}^{n-1} u\); in other words, \({\nabla}^{n} u\) is much more sparse that \({\nabla}^{n-1} u\). Taking a piece-wise polynomial function with \(n\) degree into account, it is clear that the \(n\)-th order gradient \({\nabla}^{n} u\) is sparse, but that is not the case for \(k\)-th \((k<n)\) order gradient \({\nabla}^{k} u\). This observation thus motivates us to extend Eq. (3) into higher-order gradient domains to regularize the semi-sparse signals with singularities and polynomial surfaces. In practice, the choice of \(n\) is usually determined by the property of signals.

Verification:

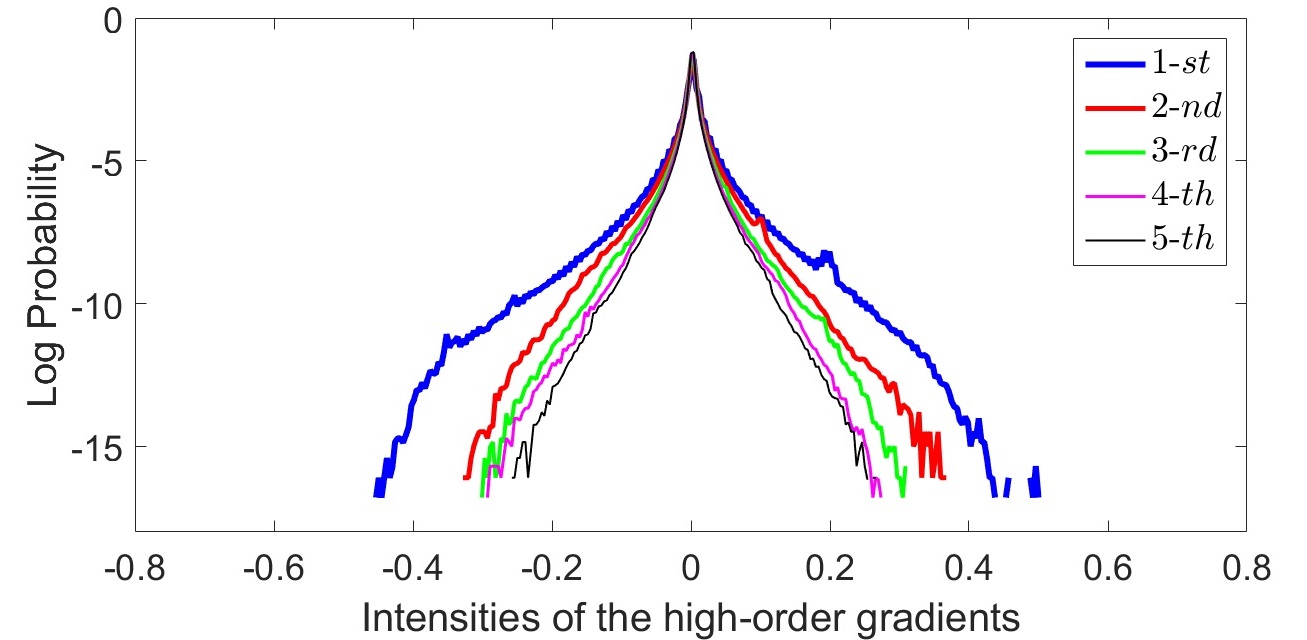

We verify the semi-sparsity prior knowledge and show its universal applicability in natural images. For the sake of this purpose, we use Kodak image dataset

The above claims intuitively motivate us to chose \(n=2\) as the highest order in most of our subsequent experiments. This choice has extra two-fold benefits: (1) \(n=2\) is the simplest semi-sparsity case, and (2) the computational cost of the proposed model is also moderate when \(n\) is small.

Semi-sparsity Smoothing Model

On the basis of Eq. \ref{eq:4} and verification of natural images, it is naturally to pose a semi-sparse minimization scheme for smoothing filters with the following generalized form,

\[\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} \mathop{\min}_{u} {\left\Vert {u}-{Af}\right\Vert}_2^2+\alpha \sum_{k=1}^{n-1} {\left\Vert {\nabla}^{k}u-{\nabla}^k (Af) \right\Vert}_2^p+\lambda{\left\Vert {\nabla}^{n} u \right\Vert}_0 \end{aligned} \label{eq:5} \end{equation}\]where $\alpha$ and \(\lambda\) are weights for balance. The first term in Eq. \ref{eq:5} is data fidelity with \(A\) adapted from Eq. (1). The second term measures the similarity of \(k\)-th (\(k<n\)) higher-order gradients. The last term indicates that the highest-order gradient \({ {\nabla}^{n} u}\) should be fully sparse under the semi-sparsity assumptions.

In practice, the choice of \(n\) is determined by the property of signals. For natural images, the observations motivate us to choose \(n=2\) as the highest order for regularization. We chose \(p=2\) for most filtering cases in view of the non-sparsity property of \({\nabla}^{k}u\) and low computational cost\footnote{It is possible to choose \(p\) for other choices, \(p=1\), for example, while the numerical solution may be computationally expensive.}. As a result, we have the reduced semi-sparsity model with the form,

\[\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} \mathop{\min}_{u} {\left\Vert {u}-{f}\right\Vert }_2^2+\alpha {\left\Vert {\nabla}u-{\nabla}f\right\Vert }_2^2+\lambda{\left\Vert \Delta u \right\Vert}_0 \end{aligned} \label{eq:6} \end{equation}\]Here, we follow the property of global filters, letting \(K\) be Kronecker kernel for simplification. This choice is based on two-fold benefits: (1) \(n=2\) is the simplest case of our semi-sparsity model, and (2) a small \(n\) is enough for a wide range of practical tasks with moderate computational cost.

Mathematically, Eq. \ref{eq:5} (or, \ref{eq:6}) can be viewed as a general extension of the sparsity-induced \(L_0\)-norm gradient regularization

In a nutshell, it is difficult for both types of traditional filtering methods to simultaneously fit a signal coexisting the polynomial-smoothing surfaces and sparse singularities features (spikes and edges), since they may either produce over-smoothing results in singularities or introduce stair-case artifacts in the polynomial smoothing surfaces. In contrast, our semi-sparsity minimization model, as demonstrated in the following experimental parts, avoids the dilemma and it is possible to retain comparable edge-preserving properties in strong edges and spikes and more appropriate results in the polynomial-smoothing surfaces, giving arise to a so-called simultaneous-fitting ability in both spikes and polynomial-smoothing regions. This property provides a new paradigm to deal with both cases in high-level fidelity, which contributes its benefits and advantages to many traditional methods.

Half-quadratic Solver

Despite the simple form of Eq. \ref{eq:5} (or \ref{eq:6}), a direct solution is not always available due to the non-convexity and combination property of \(L_0\)-norm. In the literature, such a minimization problem is solved by greedy algorithms

We employ the HQ splitting technique for the semi-sparsity minimization since it is easy to implement and has almost the least computational complexity for large-scale problems. The main idea of the HQ splitting algorithm is to introduce an auxiliary variable to split the original problem into sub-problems that can be solved easily and efficiently. For completeness, we briefly introduce the half-quadratic (HQ) splitting technique with a general \(L_0\)-norm regularized form,

\[\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} \mathop{\min}_{u} \mathcal{F}(u) + \lambda {\left\Vert Hu \right\Vert }_0 \end{aligned} \label{eq:7} \end{equation}\]where \(\mathcal{F}\) is a proper convex function, \(H\) is a (differential) operator and the \(L_0\)-norm regularized term is a non-convex, non-smoothing but a certain separable function.

By introducing an auxiliary variable \(w\), it is possible to rewrite the above minimization problem Eq. \ref{eq:7} as,

\[\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} \mathop{\min}_{u} \mathcal{F}(u) + \lambda {c(w)} + \beta {\left\Vert Hu - w \right\Vert }_2^2 \end{aligned} \label{eq:8} \end{equation}\]where \(c(w) = {\left\Vert w \right\Vert}_0\) and \({\left\Vert Hu - w \right\Vert }_2^2\) is introduced to measure the similarity of \(w\) and \(Hu\). The solution of Eq. \ref{eq:8} globally converges to that of Eq. \ref{eq:7} when the parameter \(\beta \to \infty\).

Clearly, the proposed semi-sparsity model is a special case of Eq. \ref{eq:7}, where \(\mathcal{F}(u) = {\left\Vert {u}-{f}\right\Vert }_2^2+\alpha {\left\Vert {\nabla}(u-f) \right\Vert }_2^2\) and \(H\) is the Laplace operator \({\nabla}\). The optimal solution is then attainable by iteratively solving the following two sub-problems.

Sub-problem 1:

By fixing the variable \(w\), the objective function of Eq. \ref{eq:6} reduces to a quadratic function with respect to \(u\), giving an equivalent minimization problem,

\[\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} \mathop{\min}_{u} {\left\Vert {u}-{f}\right\Vert }_2^2+\alpha {\left\Vert {\nabla}u -{\nabla} f \right\Vert }_2^2 +\beta{\left\Vert \Delta u -w \right\Vert }_2^2. \end{aligned} \label{eq:9} \end{equation}\]Clearly, Eq. \ref{eq:9} has a closed-form solution due to the quadratic form w.r.t. \(u\). Let \(\boldsymbol{D}\) and \(\boldsymbol{L}\) be discrete gradient operator and Laplace operator in matrix-form, the optimal solution \(u\) is then given by the following linear system:

\[\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} (\boldsymbol{I} + \alpha \boldsymbol{D}^T \boldsymbol{D} + \beta \boldsymbol{L}^T \boldsymbol{L}) u = (\boldsymbol{I} + \alpha \boldsymbol{D}^T \boldsymbol{D}) f + \beta \boldsymbol{L}^T w, \end{aligned} \label{eq:10} \end{equation}\]where \(\boldsymbol{I}\) is identity matrix. Since the left-hand side of Eq. \ref{eq:10} is symmetric and semi-positive, many solvers such as Gauss-Seidel and preconditioned conjugate gradients (PCG) methods

Sub-problem 2:

By analogy, \(w\) is solved with a fixed \(u\) and the first two terms in Eq. \ref{eq:6} are constant with respect to \(w\), thus it is equivalent to solving the following problem,

\[\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} \mathop{\min}_{w} {\beta} {\left\Vert \Delta u -w \right\Vert }_2^2 + {\lambda}{\left\Vert w \right\Vert}_0 \end{aligned} \label{eq:11} \end{equation}\]where \(c(w)\) counts the number of non-zero elements in \(w\). As demonstrated in many existing methods

It is also known that Eq. \ref{eq:12} is a hard-threshold operator and can be solved efficiently. The HQ splitting algorithm solves two sub-problems iteratively, providing an iterative scheme for the semi-sparsity minimization. Notice that both sub-problems have closed-form solutions in low computational complexity, which makes the \(L_0\)-norm regularized problem empirically solvable even for a large-scale of variables. The numerical results will demonstrate the effect and efficiency of the HQ splitting scheme.

The above HQ splitting scheme gives rise to an iterative hard-thresholding algorithm, the convergence of which has been extensively analyzed under convex objective function assumptions

Experimental Results

In this section, we show the simultaneous-fitting property of the semi-sparse minimization of Eq. \ref{eq:6} and its advantages in producing the “edge-preserving” smoothing results. We emphasize the “edge-preserving” property as it is vital for filtering tools to remove the small-scale details but preserve the sharpening variations. The proposed approach is compared with a variety of edge-aware filtering methods, including bilateral filter (BF)

Smoothing Filters:

We first simulate a \(1\)-D noisy signal and show the performance for persevering step-wise edges and polynomial smoothing region. As shown in Fig. (1), the cutting-edge \(L_0\) gradient minimization

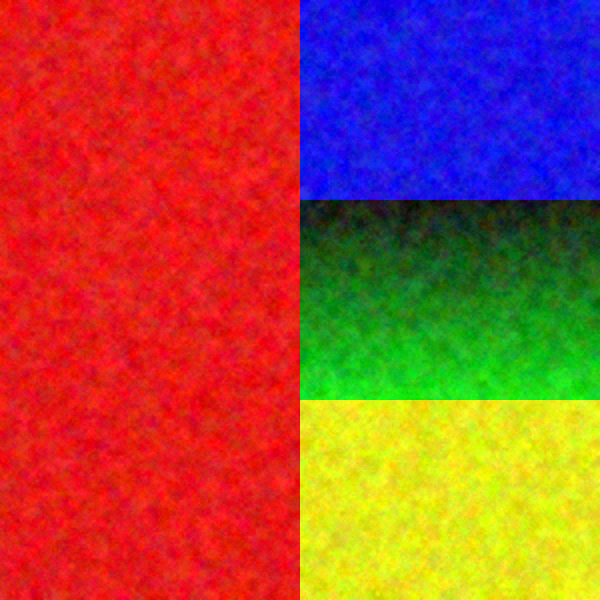

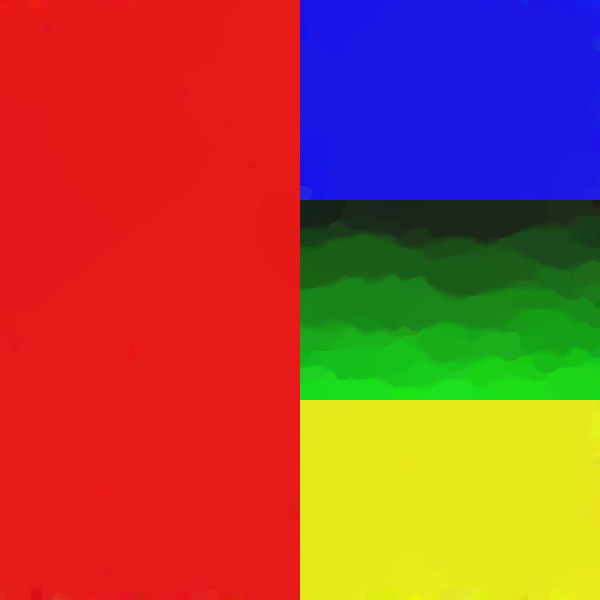

To further demonstrate the virtues of our semi-sparse smoothing filter, we compare the results of a synthesized color image that is composed of a piece of polynomial smoothing surface ({\color{green} green region}) and step-wise edges formed by different constant regions. As shown in Fig. (3), our method attains similar performance as that in the 1D case. Among them, TV method

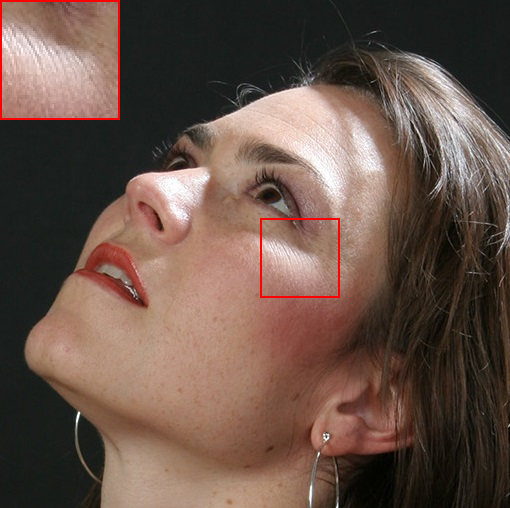

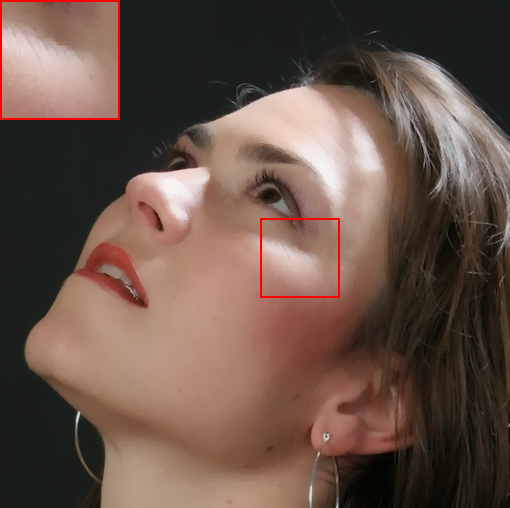

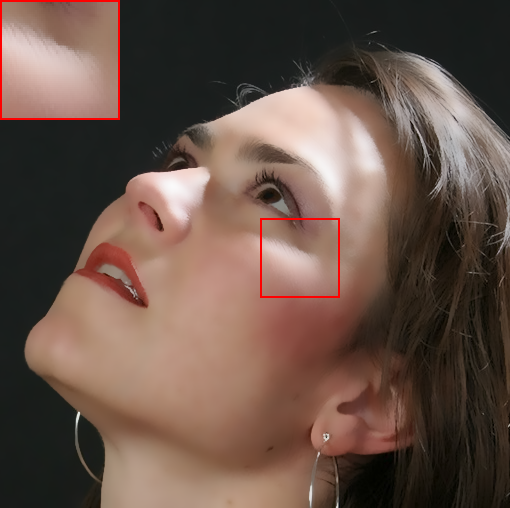

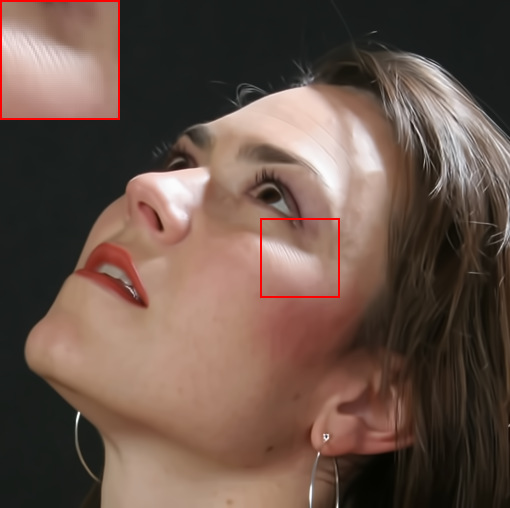

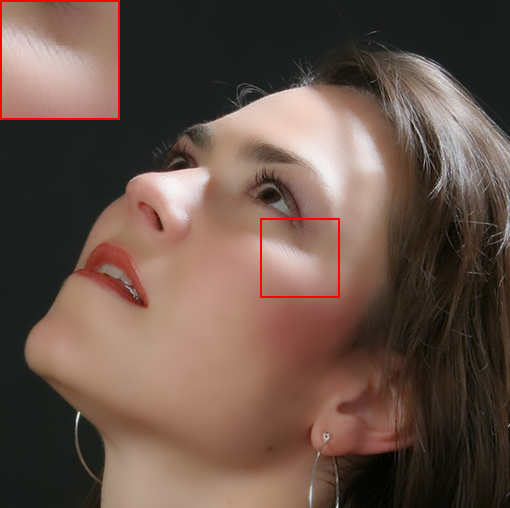

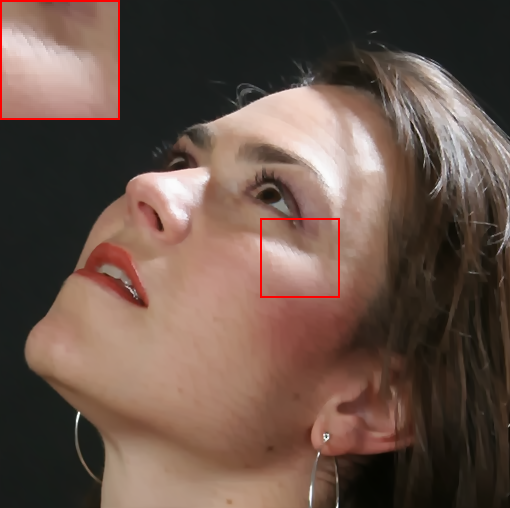

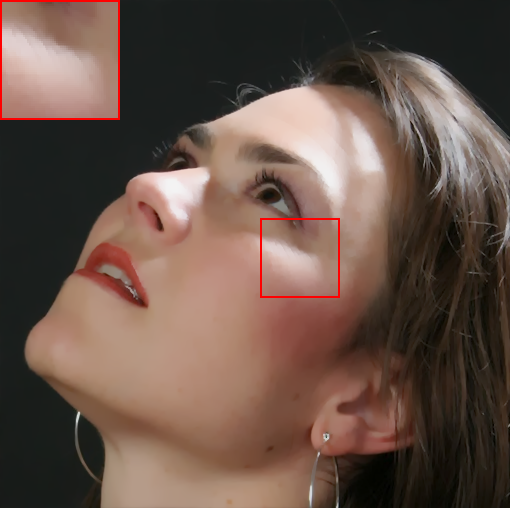

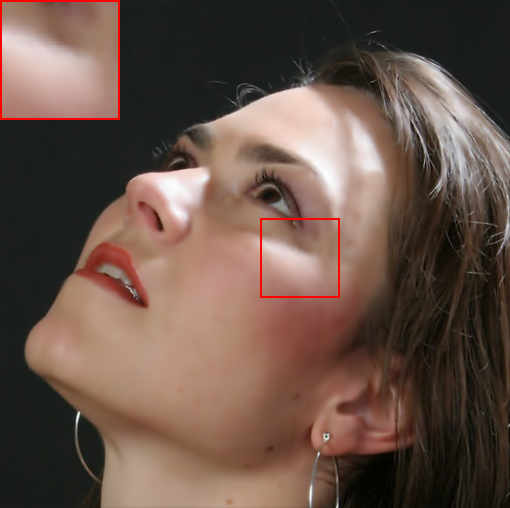

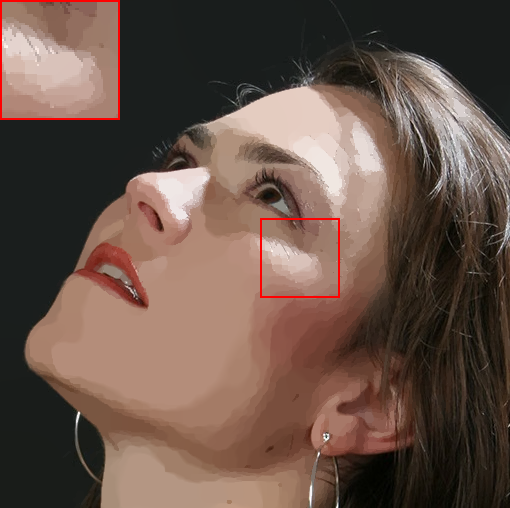

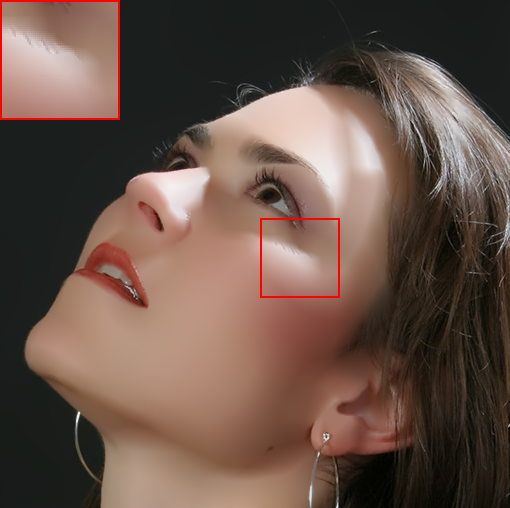

In Fig. (4), we also show the results on natural images. Specifically, we apply the filtering methods on a face image consisting of multiple polynomial surfaces (face) and strong edges (face contour and hair). In this situation, it is usually difficult to produce a visual-pleasant result. The dilemma mainly underpins the fact that both freckles and hair reveal high-frequency characteristics, while the preferred result may require to preserve the details in hair regions but to remove freckles in smoothing face regions. As shown in Fig. (4), most existing “edge-aware” filtering methods reveal limited performance in keep the smoothing balance between the high-frequency hairs and smoothing face regions. For example, bilateral filter (BF)

For complementary, we briefly explain the roles of \({\alpha, \beta}\) in controlling the smoothness of the semi-sparse minimization model. A visual comparison with varying parameters $\alpha$ and $\beta$ is presented in Fig. (5). In each row, $\alpha$ is fixed and \(\lambda\) is gradually increased to give more smoothing results; while, in each column, \(\lambda\) is fixed and $\alpha$ is increased to remove more strong local details. As we can see, \(\lambda\) plays a crucial role in controlling the smoothness of results and a larger \(\lambda\) penalizes to remove more local details and lead to more smoothing results. Over-weighting the second-order term will penalize smoothing regions as well as fine features and therefore over-smooth the details. A similar trend is observed for $\alpha$ but with a decreasing value and the results are not so sensitive to the varying of $\alpha$. Notice that $\alpha$ is reduced by \(\kappa\) time in each iteration, because the penalty for the first-order gradient in Eq. \ref{eq:5} and \ref{eq:6} play a similar role as the data-fidelity term, thus it has a relatively small impact on the global smoothing results but mainly adjusts the local details.

Higher-order Regularization:

The choice of order \(n\) in Eq. \ref{eq:5} for sparse regularization is generally determined by the property of signals. For natural images, we interpret that \(n=2\) is usually enough to give favorable results in most cases, although further improvements can be attained with the regularization over higher-order gradient domains. As shown in Fig. (6), we illustrate this observation by comparing the smoothing results in which the sparsity constraints are imposed from the \(1^{st}\) to \(3^{rd}\) orders regularizations. As shown in \(L_0\)-gradient regularization

This result can be also explained from the higher-order gradient distributions of natural images in Fig. 2, where the sparseness of the higher-order gradient signal is gradually enhanced when the order \(n\) increases. Moreover, there exists a bound of the spareness when the order \(n\) keeps increasing, as the distributions tend to be more and more similar. On the other hand, it is also clear that the gap of sparseness of the \(1^{st}\) and \(2^{nd}\) order gradients is much bigger than that of the \(2^{nd}\) and \(3^{rd}\) order gradients. A similar trend is also observed in the higher-order cases. Accordingly, we claim that the polynomial-smoothing surfaces with degree (\(n \geq 3\)) do not frequently occur in natural images, the area of which is relatively smaller than that of the \(n=2\) case. Therefore, it is usually enough to impose sparse regularization on second-order gradients for natural images. Another consideration of choosing the \(2^{nd}\) order gradient for regularization is to reduce the computation cost in many practical applications.

Applications

Similar to many existing filtering methods, it is possible to use our semi-sparsity model in various signal processing fields. We describe several representative ones involving 2D images, including image detail manipulation, high dynamic range (HDR) image compression, image stylization and abstraction.

Details Manipulation:

In many imaging systems, the captured images may suffer from degradation in details for the inappropriate focus or parameter-settings in image tone mapping, denoising, and so on. In these situations, “edge-aware” filtering methods can be used to help recover or exaggerate the degraded details. In general, it is popular to use the smoothing filters to decompose an image into two components: a piece-wise smoothing base layer and a detail layer; then either of them can be remapped and combined for reconstructing better visual results. We compare the results with the cutting-edge methods

fig5_

A multi-scale strategy is also introduced for detail enhancement. As suggested in WLS filter

HDR Image Compression:

This technique arises from the visual-friendly display of high-quality HDR images. It is similar to image details manipulation and an HDR image is usually assumed to be decomposed into a base layer and a detail layer. The base layer is piece-wise smoothing with high dynamic range contrast, which needs to be compressed for display or visual purposes. The compressed smoothing output is then re-combined with the detail layer to reconstruct a new image. The challenge here is to decouple the base layer and maintain reasonable image contrast during dynamic range compression while keeping a balance of the smoothness between the piece-wise areas and sharp discontinuities to avoid halos around strong edges and over-enhancement of spatial local details.

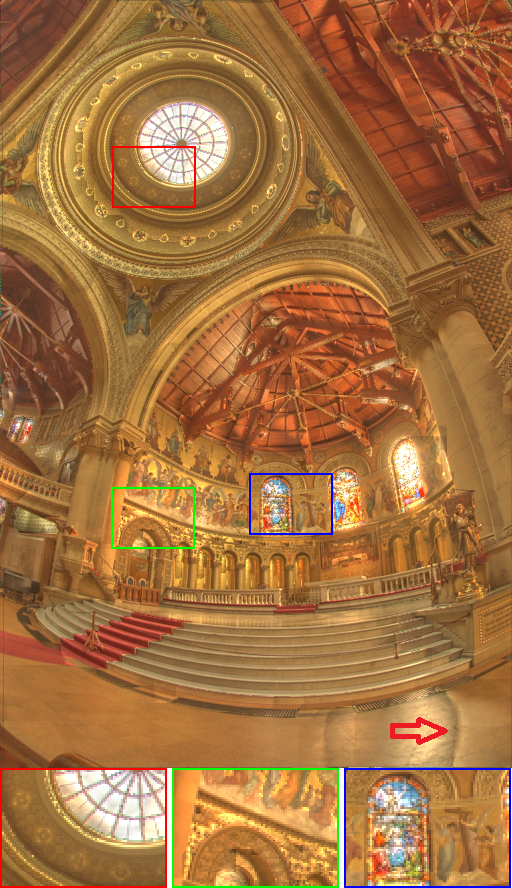

As shown in Fig. (9), bilateral filter

To verify the performance of these existing smoothing filters for HDR image compression, we further take a quantitative evaluation based on the Anyhere dataset

Image Stylization and Abstraction:

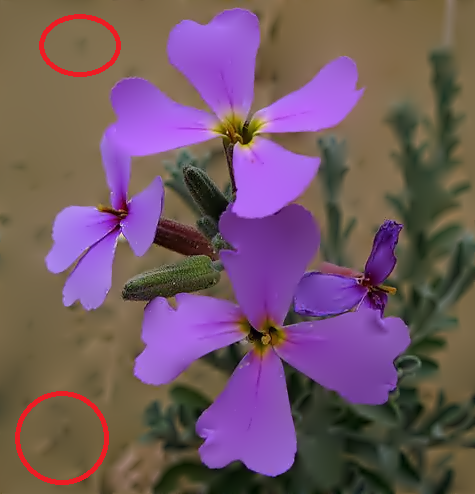

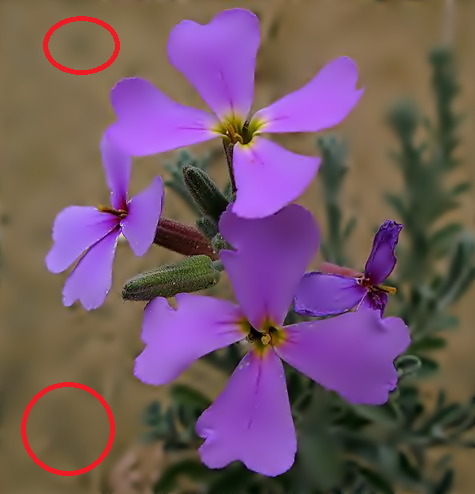

This interesting task aims to produce different stylized results or non-photorealistic rendering (NPR) of an image. In this case, the proposed semi-sparse filtering method is firstly applied for an image to remove the local textures and details; the main structure of the smoothed image is then, as interpreted in

Conclusion

This paper has described a simple semi-sparse minimization scheme for smoothing filters, which is formulated as a general extension of \(L_0\)-norm minimization in higher-order gradient domains. We demonstrate the virtue of the proposed method in preserving the singularities and fitting the polynomial-smoothing surfaces. We also show its benefits and advantages with a series of experimental results in both image processing and computer vision. One of the drawbacks is the high computational cost of solving the iterative minimization problem, which could be partially alleviated by resorting to more efficient solutions with a faster convergence rate. We leave the work for future studies.